Caleb and Leilani examine the data and stories behind student exhaustion and offer practical strategies for instructors to make a difference.

In our previous post, we outlined the top five challenges from the Ball State Student Satisfaction Survey. This post kicks off a series that will dive deep into the top five challenges students face. We will start with the most frequent challenge in recent surveys: Student Exhaustion.

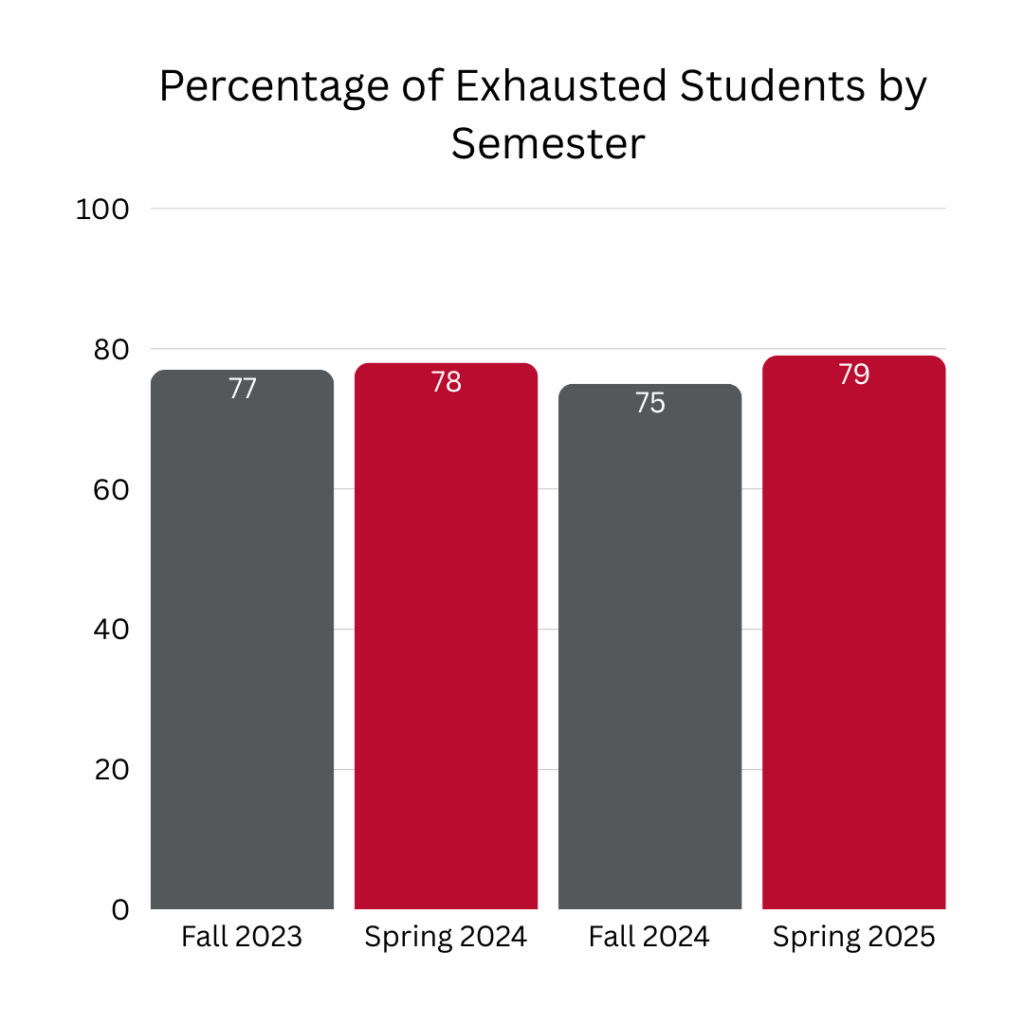

How Much Are Learners Exhausted?

Over the last two years, 6,554 students responded to our survey. Overall, 77% reported exhaustion. In spring 2025, this rose to 79% — higher than fall 2024 (75%). A similar pattern emerged in 2023-24, with 77% (fall) and 78% (spring) reporting exhaustion. Spring semesters consistently show a slight but notable increase.

Exhaustion levels are similar across graduate and undergraduate students, as well as online and in-person students. The most significant difference? First-year undergraduates (75%) report less exhaustion than second-year students (82%). Third- and fourth-year students are both at 80%, suggesting fatigue persists. This is striking and may be reflective of the extra resources directed at first-year students.

What Do Learners Say About Exhaustion?

Students describe exhaustion as systemic, a byproduct of how higher education operates. They cite overwhelming schedules, unpaid labor (e.g., internships), and sleep deprivation. One student shared:

“I don’t get enough sleep, and I’m behind in two classes, and it never lets up.”

Another student points toward struggling to balance education with meeting basic needs:

“it’s hard to balance schoolwork sometimes, especially when I need to work to provide for myself.”

Perhaps this quote cuts to the heart of these systemic issues most clearly:

“Exhaustion and fatigue have been constant companions throughout this program, not because I’m not capable, but because the course structure often demands more than what’s sustainable for working professionals, parents, or anyone with a life outside of academia.”

Beyond specific responsibilities, students describe a constant depletion of time itself. One student speaks to how this affects the overall pattern of exhaustion:

“I’ve been burnt out since my sophomore year. Some weeks are worse than others, but I often find myself out of breath or just generally exhausted. I have 12+ hour days with classes and work, and then have to go home and do homework. It’s not great.”

Others tie fatigue to coursework’s perceived value. One comment stood out:

“There’s a big difference between being challenged and being chronically depleted. When assignments pile up without clear value or connection to practical skills, it becomes draining mentally, physically, and emotionally. The exhaustion isn’t just from the workload, it’s from constantly wondering if it’s worth it.”

This highlights a disconnect. Students express a need to see and understand the value of their coursework.

How Can We help?

Considering these findings, we present tangible ways to help design our courses.

1. Provide Purpose with Transparent Design

Students crave purpose. In a previous blog, we discussed the importance of purpose statements as a part of transparent design. Transparent design involves making the purpose and instructions of an assignment clear to a learner. This can include the learning objectives tied to the assignment, the instructions for how to complete the assignment, and the criteria for how learners will be evaluated.

We have also highlighted the importance of learning objectives as a part of these purpose statements. Objectives and purpose statements are the channel to deliver meaning. If students are assigned something like an annotated bibliography, they might see this as overwhelming busy work. However, if we communicate to them that an annotated bibliography is the best way to understand, analyze, and synthesize research, they will see the larger purpose of the assignment. As teachers, these connections may seem apparent to us; however, it is always a good idea to be transparent about them to students.

2. Acknowledge Life Beyond the Classroom

We can help alleviate student exhaustion by acknowledging their lives outside the classroom. We have previously shared personal accounts of our time as new college students.which recalled various stressors of college life, including administrative and financial pressures. We also explored how beneficial clarity about the business of being a student would have been. Checking in with students about their stressors beyond your classroom is an excellent way to express care about their progress within your course. Showing compassion for them as people will help them maintain energy for your courses. It will allow you both to face the systemic problems together, rather than feel you are opposed to each other.

3. Build in Flexibility

Finally, we can address this exhaustion by being flexible in our courses. This was core to our advice when analyzing last year‘s survey data. Our previous recommendations included ways to keep the pace of your course consistent, but flexible. Specifically, we recommended keeping the time of week you expect work to be submitted flexible, expecting late submissions, and allowing multiple ways to participate.

Looking at recent data about student exhaustion also suggests this should extend to thinking about how your course fits into their larger schedules, within reason. Many students have weeks when major assignments are due in almost every class. By strategically scheduling major milestones (e.g., a midterm in Week 6 or a large paper in Week 13), we can help them avoid the worst of the semester’s “crunch times” and manage their energy more effectively. If we schedule a Midterm exam in Week 6 or make a large paper due in Week 13, this might allow students to feel a bit of relief in the usual “crunch times” of a semester.

Final Thoughts

We’ve explored student exhaustion; its patterns, causes, and small but meaningful fixes. How do you combat burnout in your work? Could those strategies be applied to your classroom?

Comments: