Written by: Jerret Barker Collections and Education Intern

Some events transcend their time and place. Stories about these events are told, and then retold, throughout the generations leading to the creation of legend. American folklore is littered with such stories: John Henry defeating the steam drill in a race between man and machine and Billy the Kid’s fatal reunion with former friend-turned-sheriff Pat Garrett. One such legend, that of Casey Jones, was instantly created in the early morning of April 30, 1900, when his train crashed into another near Vaughn, Mississippi.

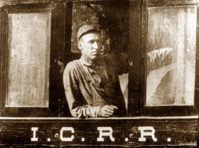

(Casey Jones in 1898. Schenectady, New York Historical Marker.)

John Luther “Casey” Jones was born on March 14, 1863 (or 1864, as records are unclear) in Missouri but moved to Cayce, Kentucky shortly after his birth.[1] His childhood hometown would later serve as the nickname in which Jones became known. Longing for the respect and praise that accompanied railroad engineers, Jones left home at 15 and slowly made his way through the railroad industry, serving as a telegrapher, brakeman, fireman, and eventually an engineer.[2] As a railroad engineer, Jones was known throughout the country for his impeccable adherence to train schedules (even if it meant increasing his speed beyond the limit) and his modified whistle, which became recognizable to anyone who heard it. So renowned was Jones that he was asked to operate trains for the visitors to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

In January of 1900, Jones took over control of the Illinois Central Railroad’s Cannonball, a fast passenger express that traveled from Chicago to New Orleans.[3] On April 29, making a late start and with orders to make up lost time, Jones and his fireman Sim Webb (the one responsible for feeding coal into the firebox to produce the steam necessary for travel) left the station on a dark and cloudy evening. Near Vaughn, Mississippi, in the early hours of April 30th, Jones noticed red lights on the back of a caboose stopped on the track in front of him. Jones, going too fast to stop, hit the airbrakes as soon as he realized something was wrong. Jones died as his engine struck the rear of the stopped caboose.[4] His last words were to tell his fireman to jump to safety, which Webb did.[5] Webb sustained minor injuries, and none of the passengers on board were seriously injured.[6]

The David Owsley Museum of Art currently displays an action-packed depiction of this deadly scene. Painted in 1939 by Edwin Fulwider, Casey Jones features Fulwider’s interpretation of Jones’s last ride. Although the actual event involved Jones hitting the caboose of another train, Fulwider portrays two speeding trains racing toward each other. Black smoke ominously billows out of both locomotives into the night sky while the tracks curve and twist, adding to the suspense of the eventual collision. Viewers can see the Vaughn train station, and even the jumping figure of Webb narrowly escaping the doomed train. This painting allows viewers to experience the drama of the collision.

(Edwin Fulwider, 1913 – 2003, Casey Jones, 1939, Oil on Masonite, Gift of Charles and Kathleen Harper, 2015.022.000, © artist’s estate)

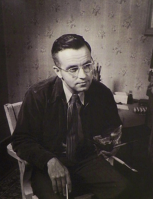

Edwin Fulwider was born in 1913 in Bloomington, Indiana. As a child, he became enamored with trains and travel as a boy, even memorizing the trains’ schedule and timing their stops across town.[7] He later graduated from the John Herron Art School in Indianapolis in 1938. Becoming a teacher later in his career, Fulwider taught at Miami University of Ohio, the John Herron Art School, and the Cornish School of Allied Arts in Seattle, Washington. He retired from teaching in 1992 but remained active as an artist until his death in 2003. Coincidently, Fulwider was able to meet and work with Thomas Hart Benton during the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, 40 years after Casey Jones operated the trains there.[8]

(Edwin Fulwider. Photo courtesy of Covington Fine Arts Gallery.)

Fulwider’s depiction of the fatal crash is just one of many honoring Casey Jones’s legacy. Songs, books, documentaries, paintings, sculptures, and a museum are dedicated to the man who lost his life trying to save his passengers on April 30, 1900. 122 years later, the legend of Casey Jones continues in art and memory. Check out Johnny Cash singing “Casey Jones,” 1963: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_XUV3HJajQ.

As always, thank you for reading the DOMA Insider and make sure to come see Edwin Fulwider’s Casey Jones piece for yourself! DOMA is open: Tuesday-Friday 9 a.m.-4:30 p.m. and on Saturday from 1:30 p.m.-4:30 p.m. Did I mention it’s free admission?

[1] “This Week in Railroad History: The Legend of Casey Jones.” National Railroad Museum. https://nationalrrmuseum.org/blog/this-week-in-railroad-history-the-legend-of-casey-jones/.

[2] Moody, James W. “Casey Jones Railroad Museum.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1966): 4.

[3] “This Week in Railroad History.”

[4] “Railroaders Hear Straight Story on Casey Jones’s Famous Ride.” Western Folklore 13, no. 2/3 (1954): 135–36.

[5] Cohen, Norm. “‘Casey Jones’s: At the Crossroads of Two Ballad Traditions.” Western Folklore 32, no. 2 (1973): 78.

[6] “This Week in Railroad History.”

[7] Gottschlich, Michelle. “Edwin Fulwider’s Early-1900s Boyhood in Bloomington, ‘A Memoir’.” Limestone Post Magazine. (2018). https://limestonepostmagazine.com/edwin-fulwiders-early-1900s-boyhood-bloomington-memoir/.

[8] “Edwin Fulwider.” Seattle Art Museum, https://art.seattleartmuseum.org/people/4752/edwin%20%20fulwider;jsessionid=E6ACB6406B0C1C77ABDE8FDAB3925BA;jsessionid=E6ACB6406B0C1C77ABDE8FD0AB3925BA.

Comments: