Thursday, November 13, Davira Taragin, the Owsley Museum’s consultative curator, gave a talk to the docents about the new contemporary craft gallery. The docents are volunteers of many backgrounds and ages who give public and private tours at the museum. Taragin’s talk put the contemporary craft gallery in context for the docents who will then be able to share this information with the public.

Taragin presented the history of the Studio Craft movement, saying that it thrived between the late 1950s to the late 1990s, but artists of diverse backgrounds still continue working with craft materials today. After WWII, many veterans used scholarships through the Servicemen’s Readjustment Bill to go to art school during the development of the studio craft movement. Studio craft uses traditional craft techniques, but in comparison to traditional craft, the aesthetic is more important than the function and bring crafts into the realm of fine art. Studio crafts were influenced by a number of art movements of the past, including abstract expressionism, minimalism, post-minimalism, light and space air, pattern and decoration, assemblage, and the imagists. The movement was also significantly influenced by the counter culture of the hippie movement. One of the points that Taragin stressed the most was that the artists of contemporary craft did not live in a vacuum, they were responding to the past and what was happening around them.

“Giants and some giants who haven’t been recognized” is what Taragin said about the artists featured in the contemporary craft gallery here at the David Owsley Museum of Art. The Owsley museum has artwork from some of the leaders in the studio craft movement, as well as work from many artists who have yet to be significantly recognized for their achievements.

(left: Landscape, 1973 by Dominick Labino, DOMA collection, right: factory glass)

Dominick Labino (1910-1987), along with Harvey Littleton, were the first to blow glass outside of a factory setting, bringing glass into the realm of fine art.

(left: Plate, 1989 by Peter Voulkos, DOMA collection, right: Right Bird Left, 1965 by Lee Krasner, DOMA collection)

The Owsley Museum also has a Plate from Peter Voulkos (1924-2002), a revolutionary in ceramics. He started out as a potter and painter, but through his inspirations from abstract expressionist painters he began to manipulate the clay with expressive energy. Through leaders like Voulkos, ceramics broke out of the role of purely functional objects into an expressive fine art.

(left: Pink and Black Moon Pot, 1980/1989 by Toshiko Takaezu, DOMA collection, right Orange, Red, Yellow, 1961 by Mark Rothko, ex. Color Field Painting)

The contemporary craft gallery displays a number of ceramic objects made by Toshiko Takeazu (1922-2011). She was greatly influenced by the color field painters of the 1940s and 50s. Her vessels, which she viewed as sculpture, are about the glaze on the surface of the form, much like how the mood set by the overlapping colors was important to the color field painters. Takeazu would also put small pieces of clay inside her forms so that they would rattle when someone lifts or holds, making them become performance pieces.

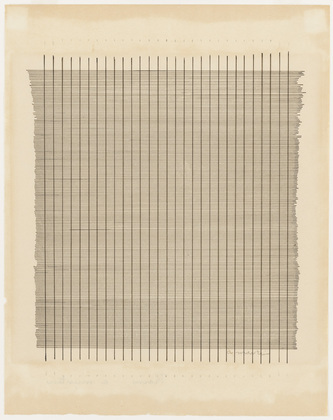

(left: Suntreader/Monophony, 1979 by Michael James, DOMA collection, right: Tremolo, 1962 by Agnes Martin minimalist painter)

Michael James (born 1949) was trained as a painter, but became interested in quilting. Although quilting was not considered a man’s medium, James embraced it and used it as a material and technique for fine art. In the work in our collection James’ influence from the minimalists can be seen in his basic color palette, and the simplified forms within this quilt.

(left: The Rope Table, 1977 by John McNaughton, DOMA collection, right: Airmchair, 1904/1908 by Josef Hoffmann, DOMA collection, example of traditional joinery)

James McNaughton (born 1943) is one of the unsung heroes that Taragin spoke of in her talk. Following the lead of pioneer maker, Wendell Castle, McNaughton laminated boards together, which was a typical process for handmade furniture of the time, cutting out the sides to shape the wood. He chose not to use traditional joining in his furniture. McNaughton’s furniture is much lighter in feeling than Castle’s ever was.

I invite everyone to come to the David Owsley Museum of Art to explore the new Contemporary Craft gallery that was curated by Davira S.Taragin. The gallery spans the studio craft movement from post WWII until the demise of the movement in the 1990s and shows how makers today continue to work with craft materials. It includes the work of several Ball State professors past and present (Patricia Nelson, Alan Patrick, Linda Arndt, Ted Neal, Ned Griner, Vance Bell, Leslie Leupp, and Marvin Reichle), as well as contemporary artists. Connections can be made between the contemporary craft gallery and many other galleries in the museum, because as Taragin said, “these artists did not live in a vacuum.”

Comments: